Summary: In practice virtually all will be identified presumptively by range. Positive identification depends on careful analysis of details of song (but questions remain about variation in song). Positive identification of silent birds is not possible on current knowledge.

The Warbling Vireos were considered a single continent-wide species until 2025, when two species – Eastern and Western – were officially recognized by AOS and eBird (Cicero 2025). The differences between these populations have been the subject of intensive research for decades, mainly in Alberta where they meet. I have spent a lot of time studying their identification over many years, with new focus in the months after the split.

Unfortunately, after dozens of hours studying photos and specimens, I have not found any diagnostic visual differences, and I am still unable to identify most photos. A combination of multiple features allows a likely identification, but not certainty. There are clear differences on average, but some photos that are surely Eastern by location look like Western, and vice versa. Measurements in-hand can be helpful but overlap extensively and only extremes are distinctive. DNA testing is the most reliable.

Song is more distinctive, and many can be identified confidently by ear, but unresolved questions about individual variation and birds that sing mixed or intermediate songs complicate the issue.

This is a very challenging identification problem and there is still a lot to learn. While I still have more questions than answers, I hope that the information presented here will help guide the discussion, which will eventually lead to more clarity.

Song

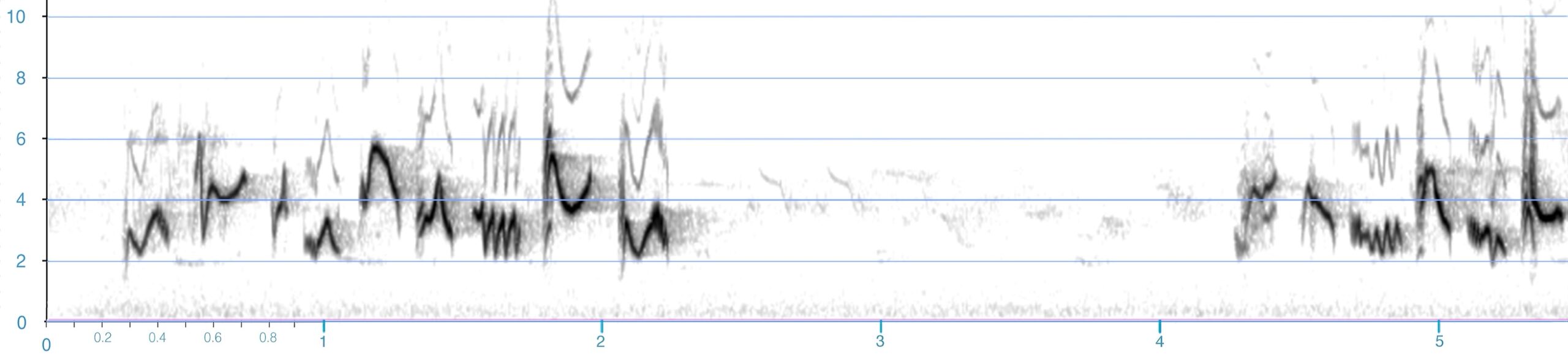

Song is the best way to distinguish these species, but still requires careful assessment of recordings. Individual variation is significant, and songs with intermediate or mixed characteristics seem to be frequent where these species meet (more details on variation here).

Song is given mainly by males on the nesting grounds about March to September. Multiple small differences combine to create a different impression.

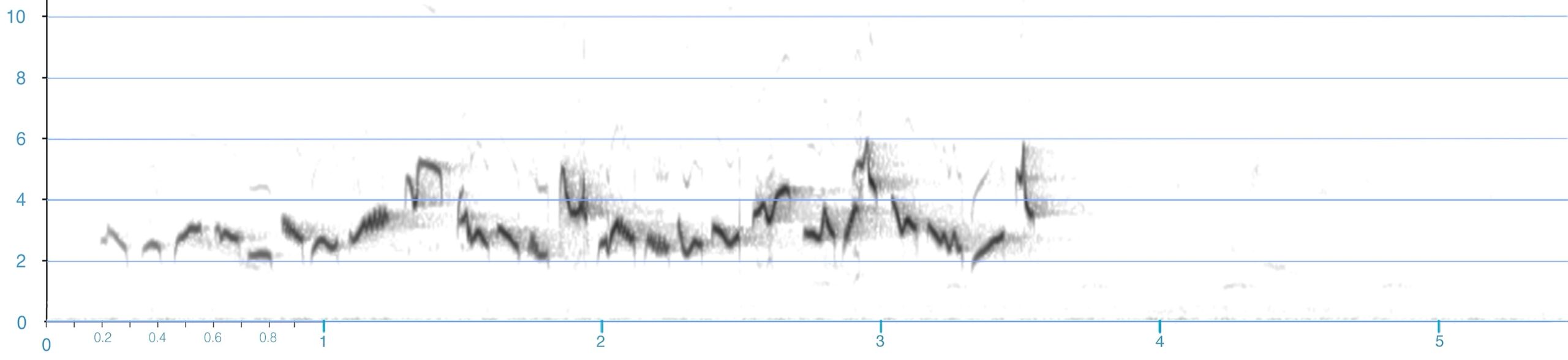

typical Eastern song

-

- more “flowing” sing-song rhythm, with more consistent pitch and tempo

- successive phrases usually only slightly higher or lower than the preceding phrase, notice the gradual rise and fall of phrases throughout the song

- each phrase shorter, with shorter pauses between phrases, overall delivery more rapid

- averages lower-pitched and in a narrow range with most phrases between 2 and 4 kHz

- most individual phrases cover a narrow frequency range

- burry phrases used only occasionally

- overall sounds more uniform with all phrases similar

- usually ends with emphatic high note

- songs average longer, but total length of song is variable, even between successive songs from a single individual

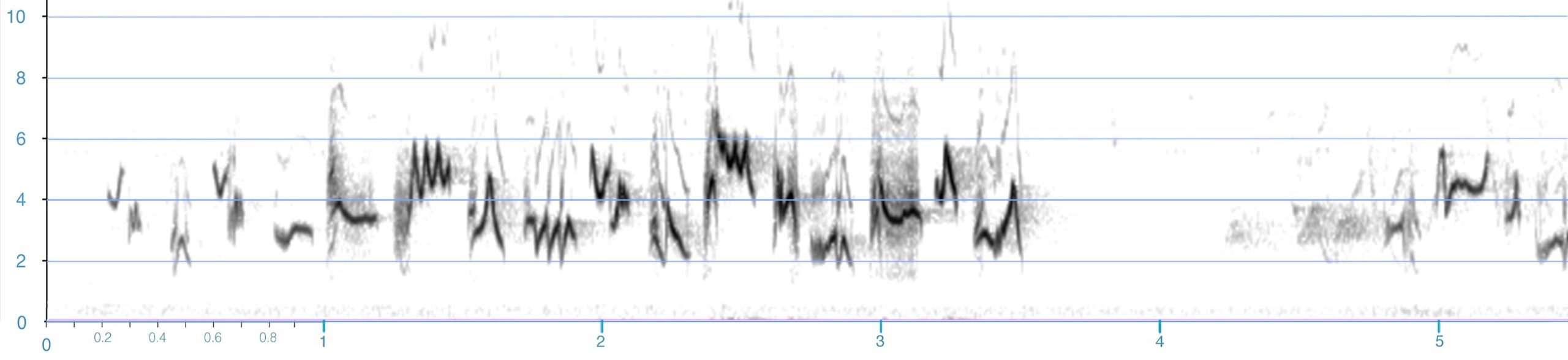

typical Western song

- more “choppy” rhythm, with more varied pitch and tempo

- successive phases often very different in pitch, with abrupt changes from high to low pitch, often roughly alternating high and low phrases

- phrases average longer, with longer pauses between, but phrases often more complex so overall tempo still sounds rapid

- sounds higher-pitched, with many phrases above 4 kHz and wider range of pitch overall

- many individual phrases cover a wide frequency range, some spanning 2 to 6 kHz

- usually includes burry phrases, often many

- sounds more varied with sharp slurs and complex phrases

- only occasionally ends with a high note

- songs average shorter, but length is variable

The examples shown here are typical and straightforward to identify, but both species are variable, successive songs are always different, and some individuals have a unique “voice”. A combination of all of the features described should reliably identify the species, but some are confusing, and careful analysis of recordings is needed to confirm an identification.

It is also worth noting that Lovell (2010) reports that among fifty individuals with both genetic data and song data, six (12%) showed a mismatch – genetically one species but with song classified as the other. Song in vireos is learned (to some extent, so this adds another source of uncertainty in identification.

Variation in song

See my supplementary post with lots of details on Variation in songs of Warbling Vireos

No difference in calls

The nasal mewing calls of both species are similar. At times I thought I detected slight differences in inflection, but after further study I think both species have a similar range of variation, and calls are not helpful for identification.

Appearance

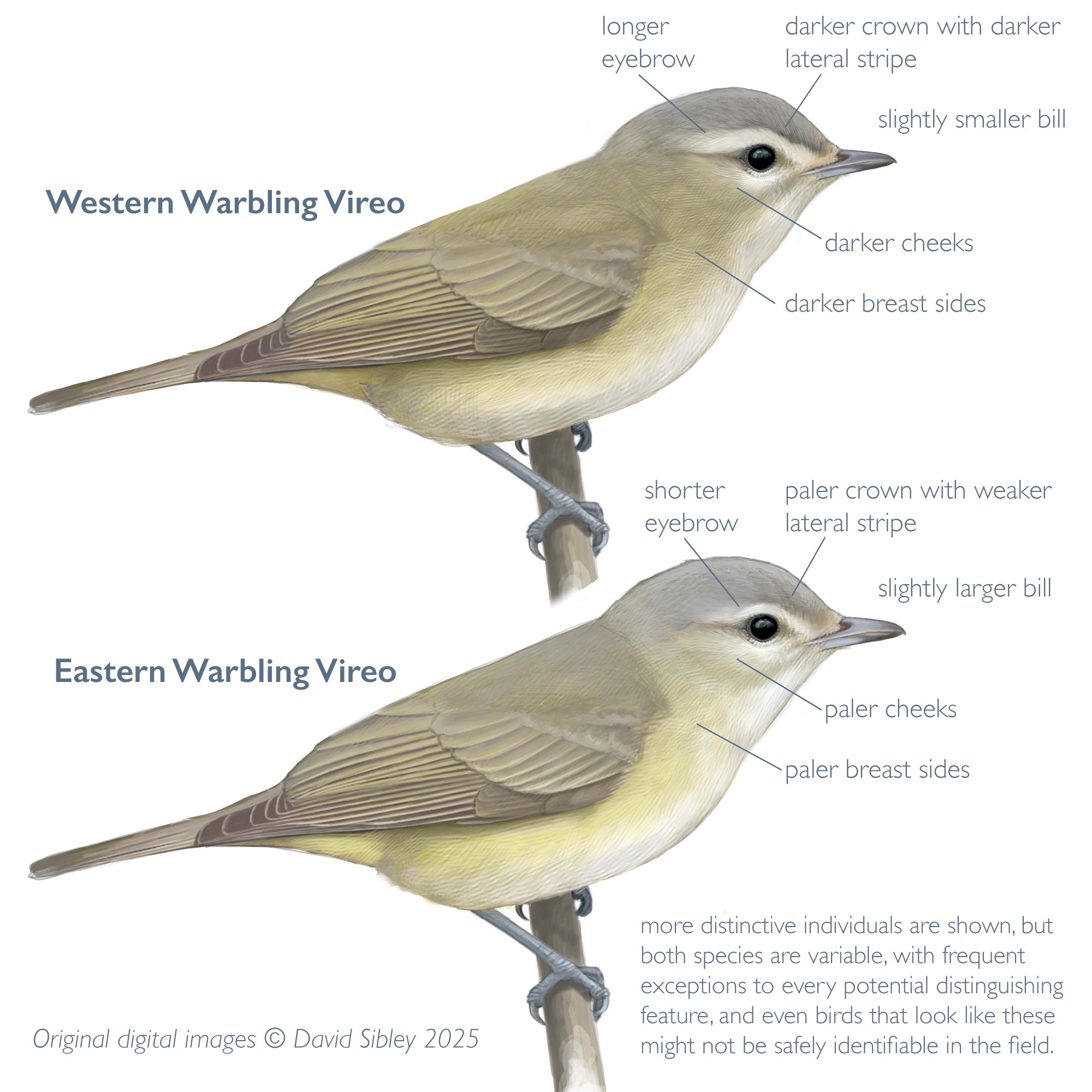

Differences between these two species in plumage and size are widely reported, but generally with unwarranted confidence and simplicity (e.g. “Western is smaller and drabber”), without conveying how subjective, subtle, and overlapping the differences are. The reality is that these species are nearly identical, there are frequent exceptions to every potential distinguishing feature, and I have found no sure way to identify them visually. The same conclusion was reached by Phillips (1991) who said “No single morphological character holds for all” Western vs Eastern Warbling Vireos.

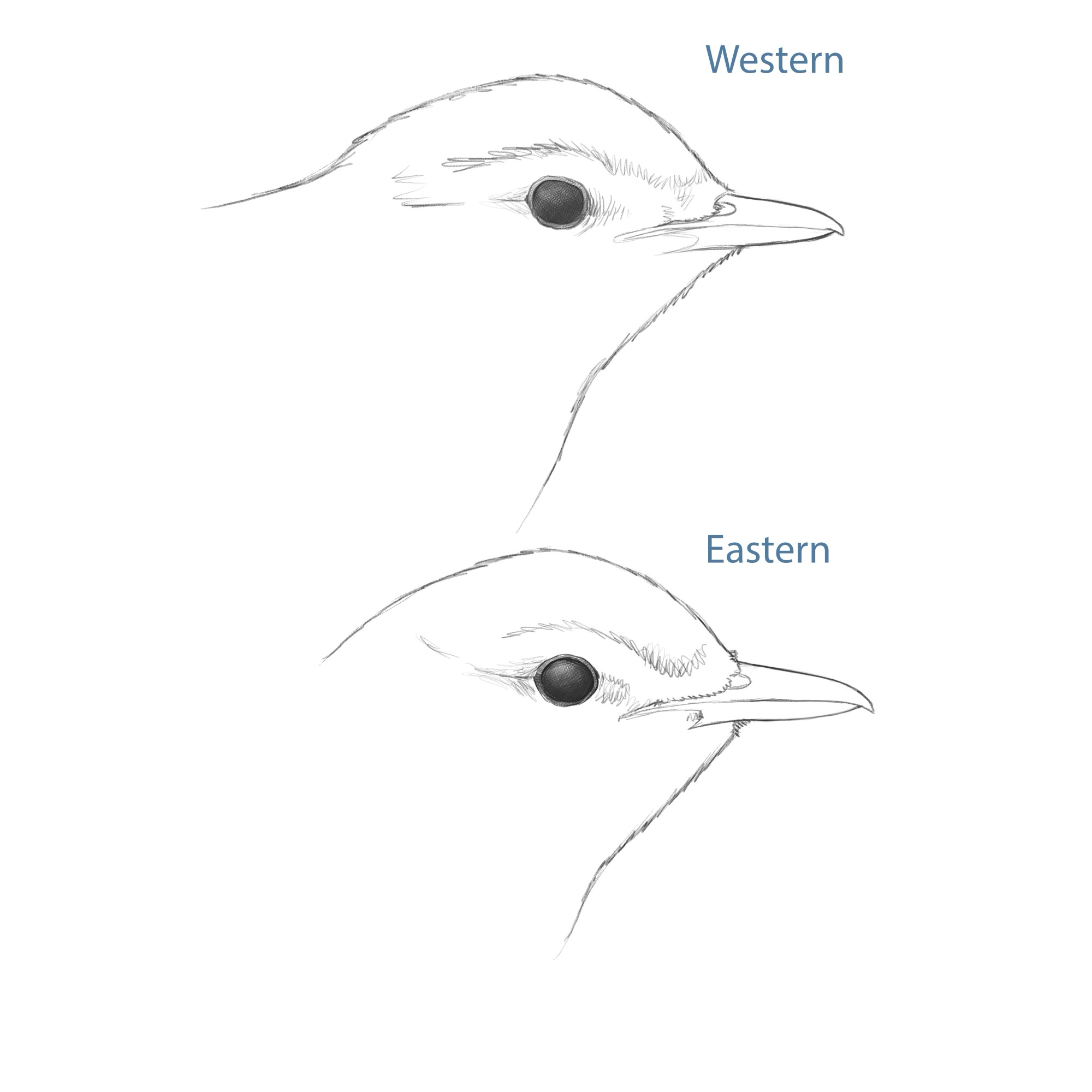

Things to focus on are crown color, eyebrow length, cheek color, and bill size. Western generally has a darker crown, a more contrasting face pattern with longer white eyebrow and darker cheeks, and a smaller bill. The presence of retained juvenile secondary coverts during fall migration is a strong point in favor of Western. A typical individual at the extremes of variation of all of these features together might be safely identified in photos. But given the extensive overlap in every feature, especially with the added variation of lighting and photo artifacts, most birds are simply not identifiable by sight.

- more distinctive individuals are shown, the “classic” examples of each species. Even these might be within the extreme range of variation of the other species, and most individuals are intermediate between these

Fresh plumage

These are brightly colored individuals, typical of many birds in fall and winter in fresh plumage

Western

- pale eyebrow averages longer behind eye, broader in front of eye

- cheeks average darker with more obvious dusky arc below eye, and more dusky color extending onto breast sides

- crown averages darker (darker than back) with more obvious dark lateral crown stripe

- bill averages smaller

- overall color averages darker with dusky yellow flanks and duller throat, but this is too variable and difficult to judge to be useful in the field

Eastern

- pale eyebrow averages shorter behind eye, narrower in front of eye

- cheeks average paler with less obvious dusky arc below eye, and little dusky color on breast sides

- crown averages paler (similar to back) with less obvious dark lateral crown stripe

- bill averages larger

- overall color averages paler with cleaner yellow flanks and brighter white throat, but this is too variable and difficult to judge to be useful in the field

Worn plumage

Both species can appear essentially plain gray, most often in spring and summer when their plumage is more worn and faded. Eastern still averages paler and more colorful, and differences in head pattern are still present, but probably even less reliable than in fresh plumage.

In worn plumage both species can be essentially plain gray, and the same details of face pattern and bill size apply. In addition Eastern tends to have a pale yellow wash on the flanks and undertail coverts, while on Western yellow is obvious only on the undertail coverts. This is subtle, variable, and difficult to judge in the field.

Bill size

Somewhat helpful at the extremes. Northern populations of Western Warbling Vireo average smaller-billed than Eastern, but there is considerable overlap, and southern populations of Western match Eastern in bill size.

In addition to smaller overall size, the bill of Western often looks slightly more tapered. Eastern often looks more even in thickness, or with the lower mandible bulging. The bill of Western is smallest in northern populations, larger (similar to Eastern) in southern populations. It averages smaller in length, width, and depth, but there is extensive overlap in all three dimensions. Different studies have emphasized bill width (narrower in Western) or bill depth (thinner in Western) as the most useful measurement, but differences are very small, overlap is extensive, and studies differ on which measurement is most helpful.

Bill color is often mentioned as a distinguishing feature, paler in Eastern, and this does show in many specimens. I simply do not see a consistent difference in bill color in photos of live birds.

Wing formula and primary tip spacing

Eastern tends to have the wingtip slightly more pointed, and this affects the spacing of primary tips on the folded wing. Eastern tends to have more irregularly and widely spaced primary tips, with a larger space between the tips of p4 and p5. Western tends to have more closely and regularly spaced primary tips. While this is evident on many birds, many more are intermediate and there is complete overlap with some of each species matching the full range of the other species. Mlodinow et al (2025 a and b) describe this a bit differently: Eastern having the space between the tips of p6 and p5 about equal to the space between p5 and p4, and Western having the space between p6 and p5 shorter. For now wing formula should be considered essentially useless for identification, pending further testing.

Phillips (1991) reports that primary 9 (the outermost long feather) falls roughly equal to the tip of p4 on Western Warbling Vireo, and closer to the tip of p5 on Eastern. This would only be useful in the hand, and needs testing to determine how reliable it is. The rudimentary 10th primary is just slightly longer than the primary coverts. Phillips reports that it is slightly longer in Eastern, but this needs confirmation.

Molt timing

Eastern typically finishes molt before fall migration on or near the breeding grounds. Western often completes molt at migration stopover sites some distance from breeding grounds. A migrating young bird with retained juvenile greater coverts in fall is more likely to be Western.

The retained juvenile coverts have small pale buff tips, looser texture, and are slightly shorter than any new inner coverts. Caution: the coverts of Warbling Vireos at all ages have pale margins, and can sometimes appear to have contrasting pale tips. Confirming the presence of retained juvenile coverts depends on careful study of feather condition, not just the impression of wingbars.

Both species molt in late summer. Adults undergo a complete molt, young birds molt body and wing coverts but retain juvenile flight feathers. The only difference is in timing. Eastern typically completes molt on or near breeding grounds before migration. Western often completes molt at migration stopover sites in Sep-Oct (mainly in the southwestern US and northern Mexico) before completing migration. Some first winter Western retain some juvenile greater coverts into Nov-Dec (eg the 2022 Cape May vagrant) but many complete molt before any migration (like Eastern), and most apparently complete molt before reaching wintering grounds.

The presence of a molt limit in the coverts is a strong point in favor of Western, but given the variability of molt timing (especially among late fall outliers) this should never be the sole basis for identification.

Hybridization

Genetically mixed individuals (hybrids and backcrosses) have been documented by DNA testing in and around the contact zone in Alberta. In Lovell et al’s (2021) sample about 6% of birds showed mixed ancestry, while Carpenter et al (2022a) found 9.2% were genetically mixed. These were concentrated in the main contact zone north of Edmonton, Alberta, but records ranged from there throughout the southern half of Alberta, east to south-central Saskatchewan, and south through eastern Montana to the Wyoming border near Yellowstone. Sampling beyond those points has been limited, so the full extent of genetic mixing is still unknown.

Needless to say, a hybrid would be impossible to identify in the field.

Range

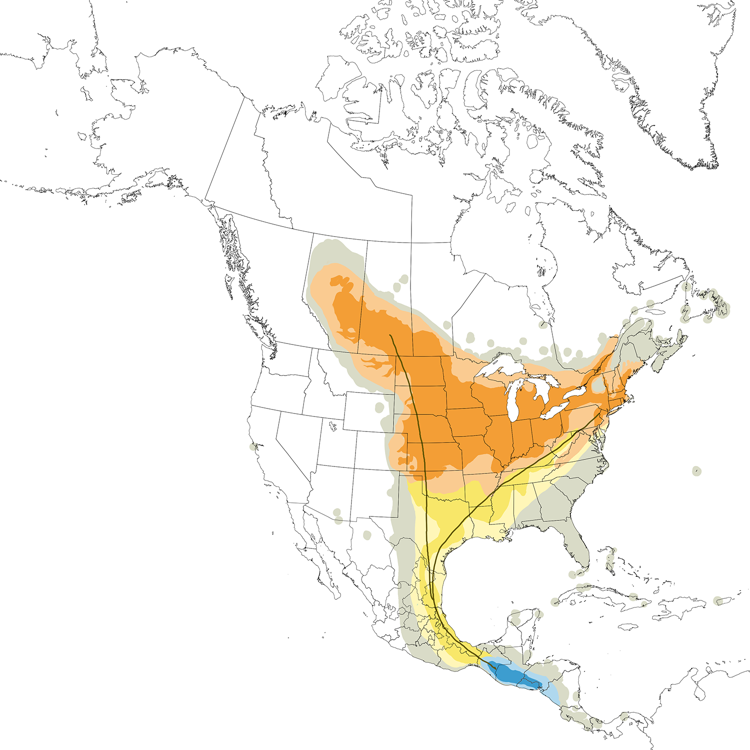

Eastern

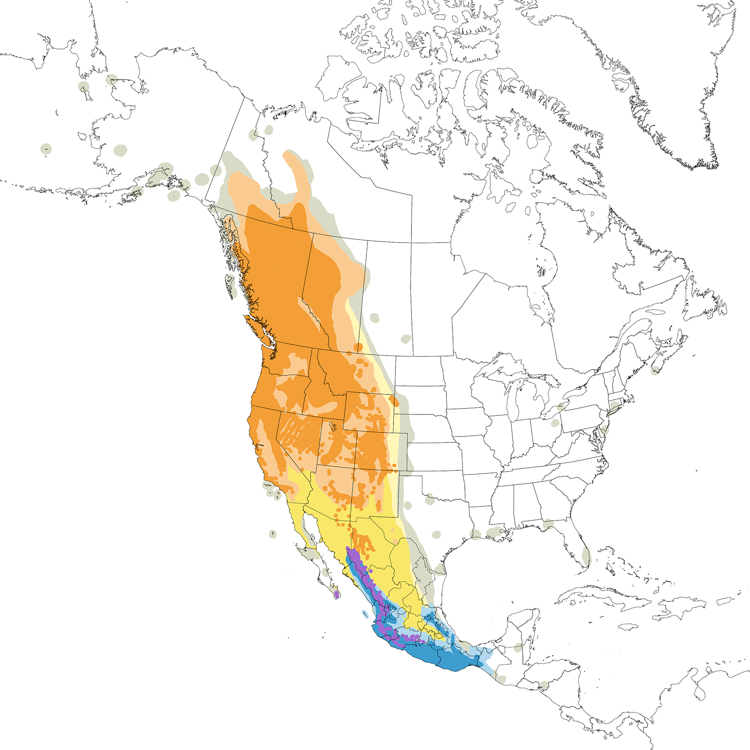

Western

The Rocky Mountains form the boundary of these species’ breeding ranges. Eastern nests east of the mountains, Western in the Rocky Mountains and west. Their nesting range overlaps just east of the Rocky Mountains from Alberta to Colorado.

Western has two genetically distinct breeding populations east of the Rocky Mountains, in the Cypress Hills of southwestern Saskatchewan and in the Black Hills of western South Dakota. In the lowlands between the Rocky Mountains and those locations, both species occur and their status is less clear. Carpenter et al 2022a show central Montana samples as genetically Western (Southwestern group), not Eastern.

Western presumably migrates mainly through the mountains. Eastern is a circum-Gulf migrant, all passing through Texas. The winter range of Western is apparently farther north than Eastern.

- nesting habitat: where range overlaps in summer Eastern is found in lowland riparian cottonwood habitat, Western in foothill canyons, aspen groves within mixed conifer woodland

spring arrival date: where range overlaps in Alberta Eastern reportedly arrives about two weeks later on average

Vagrancy

These are both long-distance migrants and it is safe to assume that each occurs as a vagrant on the other side of the continent. If they follow general patterns we should look for Western in the east in late fall, when Eastern is very rare, and Eastern in the west at known vagrant traps in fall and in late spring.

My review of eBird records and photographs in the Macaulay Library revealed lots of confusing and indeterminate records. I will comment only on a few of the more significant records here.

-

- 30 Jun 2014, Pima County, AZ – recordings and photos – https://ebird.org/checklist/S18957138 – the only fully convincing record of an Eastern Warbling Vireo west of the Rocky Mountains (the only one supported by recordings of song).

- 1 Dec 2019 Lake County, OH – https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/190900241 – with large bill, pale crown and cheeks, limited eyebrow. A late fall record with a strongly eastern-like appearance.

- 18-21 Dec 2022, Cape May, NJ – https://ebird.org/checklist/S124254725 and https://ebird.org/checklist/S124338028 . Identified as Western and currently the only record in the east that is fully convincing. It shows a consistently Western-like appearance, with small bill, dark crown, long eyebrow, strong face pattern. What sets this record apart from other Western-like birds in the east is the added support of retained juvenile coverts, and DNA from a fecal sample that reportedly “suggests” Western.

- 26 Nov 2011, Assateague Island, MD – https://ebird.org/checklist/S13542703 – small bill, long eyebrow, dark crown. This is representative of multiple late fall birds in the east that show a western-like appearance (e.g. Nov in LA – https://ebird.org/checklist/S155330192; Nov in FL – https://ebird.org/checklist/S203830594). In all of these cases I suspect Western, but currently don’t feel certain (see next record).

- 5 Sep 2024 Cuyahoga County, OH – https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/623371083 – seemingly small bill, dark cheeks, dark crown, long eyebrow. This photo blends right in to a lineup of Western Warbling Vireos, but it’s from early September in Ohio. It is presumed Eastern based on that, and an example of how difficult it is to identify these two species in photos. There are many other photos from the east in spring and fall showing similarly western-like birds.

- 24 Oct 2013, Bon Portage Island, NS, banded, measured and photographed https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S15576234 . Identified as Western by measurements, but bill size, eyebrow, and cheek color are all more eastern-like.

- 19 Nov-4 Dec 2021, Monterey County, CA – photos https://ebird.org/checklist/S97804606 – Identified as Eastern, but long eyebrow, dark crown, thin bill, and dark cheeks all look more western-like.

I am not claiming to know what species these birds are, only trying to report my objective assessment of their appearance, and describing them as “eastern-like” or “western-like” rather than naming species. Until we know more about identifying Warbling Vireos most records should be listed as “Warbling Vireo sp.”

Sources

Browning 2019 – M. Ralph Browning. 2019. A review of the subspecific and species status of warbling vireo (Vireo gilvus). Oregon Birds 45: 89-99. https://oregonbirding.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/OB-45.2-2019-Fall.pdf

Browning 2021 – M. Ralph Browning. 2021. Toward Clarifying The Wyoming Ranges Of The Vireo gilvus Complex. Western Birds 52: 240–251. – https://doi.org/10.21199/WB52.3.4

Carpenter et al 2022b – A. M. Carpenter, B. A. Graham, G. M. Spellman, and T. M. Burg. 2022. Do habitat and elevation promote hybridization during secondary contact between three genetically distinct groups of warbling vireo (Vireo gilvus)?. Heredity 128: 352-363. – https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-022-00529-x

Carpenter et al 2022a – Amanda M Carpenter, Brendan A Graham, Garth M Spellman, John Klicka, Theresa M Burg. 2022. Genetic, bioacoustic and morphological analyses reveal cryptic speciation in the warbling vireo complex (Vireo gilvus: Vireonidae: Passeriformes). Zool J Linn Soc 195: 45-64. – https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlab036

Cicero 2025 – Carla Cicero. 2025. Treat Warbling Vireo Vireo gilvus as two species. AOS Checklist committee proposal. – https://americanornithology.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/2025-C.pdf

Floyd 2014 – Ted Floyd. 2014. Documentation by sound spectrogram of a cryptic taxon, _Vireo g. gilvus_, in Boulder County, Colorado. Western Birds 45; 57-70. – https://archive.westernfieldornithologists.org/archive/V45/WB-45\(1\)-Floyd.pdf

Howes-Jones 1985a – D. Howes-Jones. 1985. Relationships among song activity, context, and social behavior in the warbling vireo. The Wilson Bulletin – http://www.jstor.org/stable/4162033

Howes-Jones 1985b – D. Howes-Jones. 1985. The complex song of the Warbling Vireo. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63; 2756-2766.. – https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z85-411

Lovell 2010 – S. F. Lovell. 2010. Vocal, Morphological, and Molecular Interactions between Vireo Taxa in Alberta. Doctoral dissertation, University of Calgary, Department of Biological Sciences. https://ucalgary.scholaris.ca/items/468a37d9-f0fc-4773-85f3-6addca3ecbb8/full

Lovell et al 2021 – Scott F. Lovell, M. Ross Lein, Sean M. Rogers. 2021. Cryptic speciation in the Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus). Ornithology 138: 1-16. – https://doi.org/10.1093/ornithology/ukaa071

Mlodinow et al 2025a – Mlodinow, S. G., A. M. Carpenter, T. Gardali, G. Ballard, P. Pyle, G. M. Kirwan, S. M. Billerman, and A. J. Spencer (2025). Western Warbling Vireo (Vireo swainsoni), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wewvir2.01

Mlodinow et al 2025b – Mlodinow, S. G., A. M. Carpenter, T. Gardali, G. Ballard, P. Pyle, A. J. Spencer, G. M. Kirwan, and S. M. Billerman (2025). Eastern Warbling Vireo (Vireo gilvus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (B. K. Keeney, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.eawvir1.01

Phillips 1991 – Allan R. Phillips. 1991. The Known Birds of North and Middle America Part II: Bombycillidae; Sylviidae to Sturnidae; Vireonidae. Denver, Colorado. Allan R. Phillips

Spencer 2012 – Andrew Spencer. 2012. Identifying Eastern And Western Warbling Vireos. Earbirding blog post. https://earbirding.com/blog/archives/3667

Voelker and Rohwer 1998 – G. Voelker, Sievert Rohwer. 1998. Contrasts in scheduling of molt and migration in Eastern and Western Warbling-Vireos. Auk 115; 142-155.

Thanks very much for this thorough review, David. One question has been bugging me. If it’s currently not possible to distinguish these two species with any degree of confidence when they’re not singing, how do we know their nonbreeding distributions, as depicted in the maps you shared? Along the Pacific coast of Oaxaca, Mexico, I am frequently seeing warbling vireos at this time of year, but with one recent exception I have not heard any singing. I’ve been seeing many reports on eBird in this region presumptively identified as Western Warbling Vireo by range, but almost all without convincing documentation. I presume that the best practice (at least until we know more) would be to report overwintering birds as Eastern/Western Warbling Vireo, except in those rare cases when they sing. Your thoughts, please?