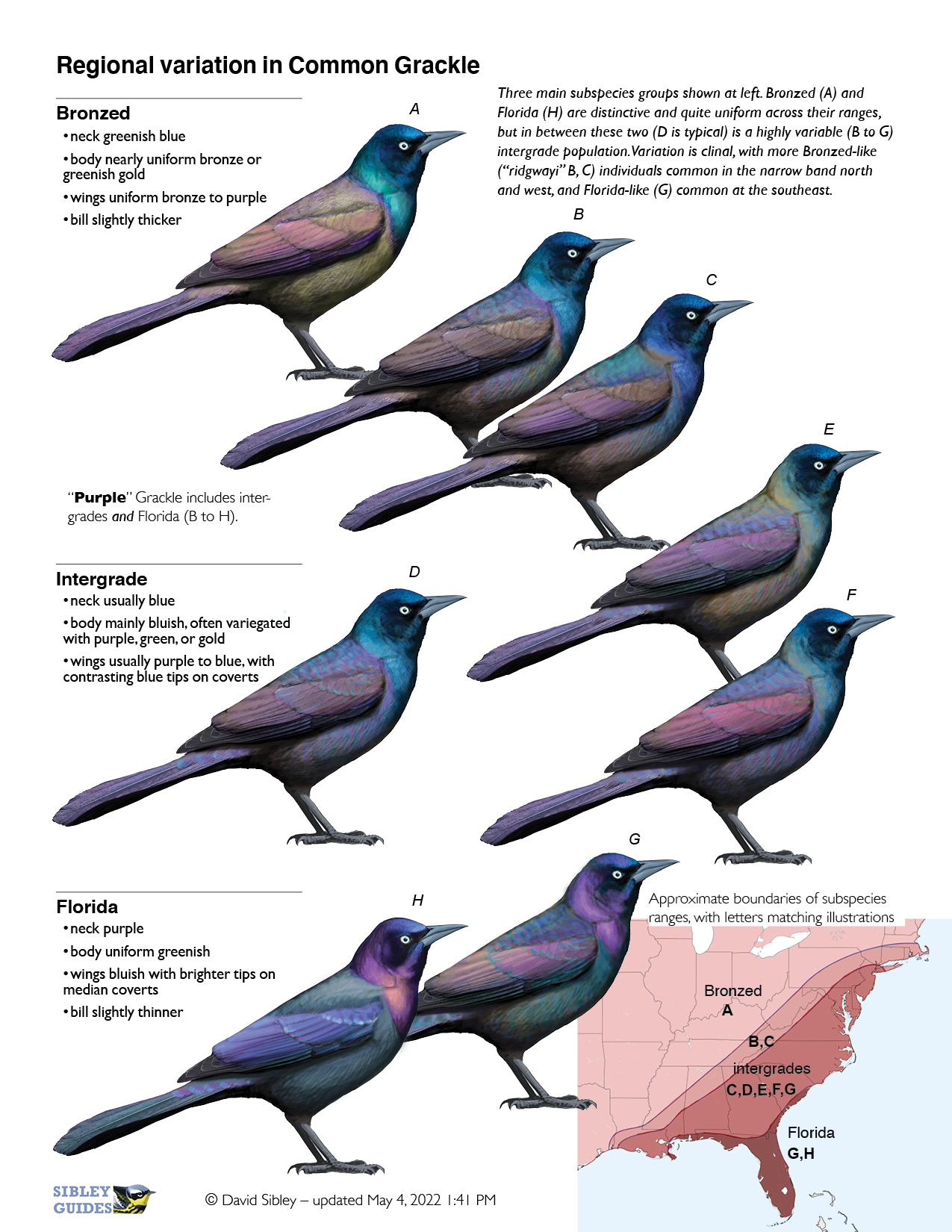

Common Grackle is a familiar backyard bird almost everywhere east of the Rocky Mountains, and shows some fairly striking regional variation in color. This variation involves mainly the colors of iridescence, and is most obvious in males. Females of the two extremes are readily identified, but the full range of intermediates is only apparent in males. Despite a series of detailed studies by Frank Chapman (1892 to 1940) this variation is not well understood by birders today, and is obscured and even misrepresented by simplified subspecies treatments in e.g. eBird and the Sibley Guides.

Overview of variation

One subspecies – Bronzed – is found across most of the species’ range with essentially no variation. Everywhere north of the Gulf Coast and west of the Appalachians is occupied by this subspecies, which is very consistent in appearance from Alberta to Newfoundland and south to Georgia and Texas. Other subspecies occur only in the coastal plain and Piedmont from Louisiana to Massachusetts.

Like Bronzed, the Florida population is distinctive and consistent in appearance, found in Florida and in a narrow band along the coast to Louisiana and South Carolina. In between these two distinctive types, in a wide band from Louisiana to Massachusetts, is a variable population of intermediate birds. This can be thought of as a broad zone of intergradation between Bronzed and Florida grackles, and the average appearance of birds in this band changes gradually from more Florida-like to more Bronzed-like as one travels northwest across the band.

Even after painstakingly documenting the clinal nature of the variation, Chapman separated this band into two even narrower bands. The northern-western band he named subspecies ridgwayi. It is found adjacent to Bronzed grackles, and is similar to them except for having some non-bronze color (usually blue-green) on the back and sometimes flanks. Head color and wing color are a little more variable than on Bronzed.

It is important to understand that ridgwayi is not a uniform population. Not all birds within this narrow band look the same. Some are more Bronzed-like and some show more intergrade features. It does not fit the modern definition of a subspecies, Chapman simply used the label ridgwayi to identify individuals within the broader population that had more blue color than typical Bronzed. Similar birds fitting the characteristics of ridgwayi can also be found south and east into the broader band of intergrades. This narrow zone, then, is simply the area where intergradation begins and some otherwise Bronzed-like birds show a blue back. More variable and colorful features show up farther south and east into the broader band of intergrades.

The southern-eastern band in this intergrade zone was given the name stonei by Chapman. This is the most variable group, with appearance ranging from nearly Bronzed-like to essentially Florida-like, and everything in between, as well as some variations of color not seen in either Bronzed or Florida. Variation is clinal, with Bronzed-like birds more frequent north and west and Florida-like birds more frequent to the south and east. Single locations (such as Princeton, New Jersey) can hold the full range from nearly Florida-like to nearly Bronzed-like, and these are indistinguishable from specimens from the opposite end of the intergrade zone in Louisiana (Chapman 1940).

A note about Iridescent colors

It’s worth mentioning that iridescent colors (as on these grackles) are produced by the microscopic structure of the feather, not by pigments. The precise dimensions of the structure correspond to the wavelengths of light that are reflected, and that determines the colors we see. These structure-based colors don’t “blend” in predictable ways like pigment-based colors, and this helps to explain why the iridescent colors of intergrade grackles are so variable and sometimes unexpected.

How to categorize the variation

There is no dispute that Bronzed and Florida grackles are distinctive and relatively uniform populations. There is less agreement about how to classify the band of intermediate birds. Chapman placed them in two subspecies, but both are variable populations that include many individuals similar to Bronzed or Florida. The presence of a few essentially typical Florida-like grackles north to New Jersey and west to Louisiana makes it difficult to draw a line at the edge of the range of Florida grackle, and this led Chapman to group the stonei intergrades with Florida as “Purple” grackle, distinct from Bronzed. He considered the true intergrade zone to be the narrow band that he labelled ridgwayi, where Bronzed begins to mix with “Purple”.

This treatment is more or less followed by eBird and others today, recognizing two subspecies groups of Common Grackle – Purple and Bronzed. The concept of a broad “Purple” grackle – lumping stonei and Florida as proposed by Chapman – obscures the difference between the relatively consistent appearance of grackles in Florida and the extreme and clinal variation north and west. The fallacy that there are just two kinds of Common Grackles ignores the intergradation, and becomes even more misleading when birders spot an intergrade ridgwayi at the boundary with Bronzed and label it as “Purple” grackle. This effectively divides Common Grackle into “Bronzed” and “everything else”.

This is not entirely wrong. It is absolutely worth recording the presence of a blue-backed ridgwayi grackle among Bronzed, and currently the only option in eBird is to call it “Purple”. But we should not lose sight of the fact that this is one small part of a complex tapestry of variation that is not easily categorized. We need to classify things, but creating labels forces us to make choices which are often arbitrary. I think it would be more accurate to recognize three groups – Bronzed, Florida, and intergrades – with the understanding that these blend together and the intergrade population changes gradually across its range. The best solution is to document the variation that you see with descriptions, photos, sketches, etc. and enter them all as Common Grackle. Describing which category your sightings might go in, and the evidence pro and con, is much more helpful than simply giving them a label without explanation.

Movements and vagrancy in Common Grackle subspecies

For the most part subspecies of Common Grackle can be identified by location. The only highly migratory subspecies is Bronzed, and large numbers of Bronzed grackles move south and east in winter. Some flocks move into the range of other subspecies, but this overlap is limited. Even at Cape May, NJ, not far south and east of the range of Bronzed grackles, Bronzed is an irregular and scarce winter visitor, appearing mainly when heavy snow cover or extreme cold forces wintering flocks to move. Chapman (1940) reported that he had not found a single record of any “northern” grackle in Florida.

A challenge for observers in Florida now: Look for the first state record of Bronzed grackle!

Florida grackles are entirely sedentary. Populations of intergrade grackles from New Jersey to Louisiana are sedentary or (in locations with colder winters) short-distance facultative migrants, and would not be expected to wander far from their home range. These sedentary habits, combined with the variability of the population, means that a more Florida-like grackle anywhere outside their core range is almost certainly a local variant, either a short-distance wanderer from a nearby population, or an extreme genetic expression from within the local population, and not a vagrant from Florida.

References

Chapman 1892 – Frank M. Chapman. 1892. A preliminary study of the grackles of the subgenus Quiscalus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 4: 1-20 – [pdf]

Chapman 1935/a – Frank M. Chapman. 1935. Further remarks on the relationships of the grackles of the subgenus Quiscalus. The auk 52: 21-29 – [pdf]

Chapman 1935/b – Frank M. Chapman. 1935. Quiscalus quiscula in Louisiana. The auk 52: 418-420 – [pdf]

Chapman 1936 – Frank M. Chapman. 1936. Further Remarks on ”Quiscalus” with a Report on Additional Specimens from Louisiana . Auk 53: 405-417 – [pdf]

Chapman 1939 – Frank M. Chapman. 1939. Nomenclature in the Genus ”Quiscalus”. Auk 56: 364-365 – [pdf]

Chapman 1940 – Frank M. Chapman. 1940. Further Studies of the Genus ”Quiscalus”. Auk 57: 225-233 – [pdf]

Hello DAS. Pete Capainolo from AMNH doing work on Common Grackle. Great piece and painting! Would like to talk about some of it, please get in touch at your convenience. Thanks

Thanks for the clear and really interesting analysis! Here’s a cool paper, by S. Y. Yang and R. K. Selander, that’s now more than 50 years old:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2412354?origin=crossref

Some of Yang and Selander’s hypotheses could be tested with eBird data (and with the excellent reference material presented above) from the 21st century. Would love to see that work done.

(Note: An immediate challenge, going forward, would be to compare the status historically in Louisiana of what Yang and Selander call Q. q. quiscula vs. the present interpretation. Fortunately, as Yang and Selander note, there is a good record from Louisiana, and I think it would be doable.)