In a footnote here I mentioned that blackish feathers can appear gray because of powder down, and now I will offer a little more explanation.

Powder down feathers are small, specialized downy feathers that grow continuously and are never molted. Their tips disintegrate into tiny particles of keratin forming a very fine powder somewhat like talcum powder. This powder is slightly oily, and adheres to the feathers. Only a few families of birds have powder down – herons, parrots, tinamous, and bustards – and it is thought that the powder helps with waterproofing and feather care, absorbing mud or other foreign substances on the feathers so that it is easier for the bird to preen away.

Powder down is usually whitish or yellowish (red in one species of bustard), and the effects of the powder can often be seen in a bird’s plumage. The Palm Cockatoo (wikipedia) of Australia is reportedly a glossy black bird, but a thorough dusting with powder renders its plumage slate-gray. Mealy Parrot is another species that shows plumage obviously “frosted” with pale powder. It is possible that the orange patches shown by Cattle Egrets in “breeding plumage” are at least partly the result of colored powder on those feathers. (Kempenaers et al., 2007)

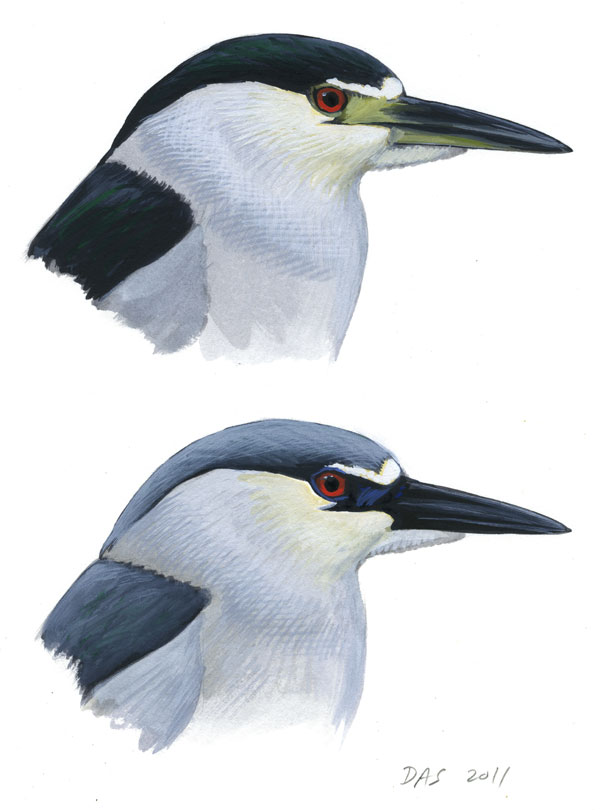

Among North American birds, the Black-crowned Night-Heron offers one of the best opportunities to see the effects of powder down. The crown feathers are actually glossy black, but often look slate-gray, presumably because of an abundance of powder. It has been reported that the gray color is typical of breeding season birds (in Africa), implying either that the powder is produced more abundantly then or that the birds actively apply it to their crown at that season. My informal review of photos does not show a clear link to season in North American birds, but I first noticed a very gray crown on a nesting night-heron in Georgia just last year, so I suspect it is a breeding season feature here, as it is in Africa.

I’d be interested to hear more about this from anyone with more experience.

References

Kempenaers, B., K. Delhey, and A. Peters. 2007. Cosmetic Coloration in Birds: Occurrence, Function, and Evolution. The American Naturalist 169, Avian Coloration and Color Vision, pp. S145-S158 http://www.jstor.org/stable/4125308

Very interesting post! I have heard a few stories about owls colliding with cars, porch windows, and the like, after which an imprint of the owl’s feathers was visible on the struck surface. I’ve always assumed that this was powder down being left behind, but I don’t know for a fact whether or not owls possess powder down.

Hi Matt, According to Kempenaers et al, owls are not one of the groups known to have powder down. It’s possible that they do have it and it hasn’t been identified yet, but more likely that the imprints they leave behind are just feather oil and dust.

I have had ghost impressions on my windows from dove collisions, and they can provide very detailed outlines. Do pigeons and doves also have powder down?

I recall reading in some older British publications that the reflective coloration on the upperwings of terns is the result of powder down and the dark area on the upperwing of Common Tern is caused by the loss of the powder down as a consequence of wear. Is that true?

And lastly, do these powder down feathers grow out of their own feather follicles or can they piggy-back on the follicles of other feathers?

Thank you for the helpful information.

Hi Joe, Yes, pigeons and doves do have powder down (according to Kempenaers et al). The full list of families is herons, storks, bustards, pigeons, woodpeckers, frogmouths, parrots, and cockatoos. One of the interesting facets of this is that it shows up in a few unrelated families. Kempenaers et al suggest that powder feathers have evolved separately several times, but I’m not sure how they rule out the possibility that it’s an ancestral trait that is only expressed in a few families.

At least some pigeons have a modified type of powder feathers called “fat quills”, which function just like an oil gland, releasing oil when preened; and in some cases produce oil and powder. It may be that all powder feathers produce both oil and powder, with some species producing mostly powder and others mostly oil, but I’m just speculating there.

Terns do not have powder down. The silvery “sheen” on their primaries is laid down when the feather grows and gradually wears away.

I don’t know the answer to your last question. In most families the powder feathers are scattered throughout the plumage, but in some such as herons and frogmouths they grow in dense patches mainly on the underside of the body.

Here is a recent rather spectacular image of an owl imprinted in a window and attributed to “powder down.”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-14111152

There is indeed some old published evidence for powder-down on owls:

W. DeW. Miller in 1924 (p. 329 of “Further notes on ptilosis.” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 50:305-331) wrote that the Barn Owl has “a well-marked patch [of powder down] on each side of the rump, as well as scattered downs on the interscapular and scapular regions and on the breast.”

Asa Chandler in 1916 (p. 258 of “A study of the structure of feathers, with reference to their taxonomic significance.” University of California Publications in Zoology 13(11):243-446) wrote that, “I have also found it [i.e., powder-down] in the burrowing owl.”

Both of these are cited by Ernst Schüz in his classic 1927 review of powder-down ( Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Puderbildung bei den Vögeln. Journal für Ornithologie 75:86-223), although Schüz seems to dismiss Chandler’s statement as too vague. Schüz also mentions seeing powder-downs on several species of owls himself, but he does not consider owls to be the best examples of classic powder-down.

I am not aware of any evidence that owls use powder for cosmetic functions, and so it is not surprising that there would be no mention of owls in the Delhey et al. article.

Pingback: Why is the ibis often grubby, and the egret always clean? | Paperbark Writer

Dear Mr. David Sibley,

I am definely not an “anyone with more experience”. My co-workers and I are working on plumages of egrets in Thailand in A1 poster format. Krieng Meemano and I enjoy your post at https://www.sibleyguides.com/2012/08/determining-the-age-of-white-egrets-and-herons-in-late-summer/ very much. Each co-worker usually observes birds for years before even knows Thai Bird Plumage Guide project. Our completed works are at https://www.facebook.com/ThaiBirdPlumageGuide. May I share the link of this post to our readers there, please? We see things that we cannot explain a lot. For Cattle Egrets, we have different species in Thailand. The orange part is more extensive, covering bigger area. With changing in colour of the same feather, and with no moult, added on substance is the best explanation. We do not know which part of the bird gives that substance. We use only photographs of free birds. I hope that new data from bird banders will answer this question soon. I might even be able to persuade a friend that it is an interesting study.

Thank you for books and blog. I learn a lot from you.

Chuenchom Hansasuta

http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anne_Peters/publication/24411811_Cosmetic_coloration_in_birds_occurrence_function_and_evolution/links/09e415067ac28b98a1000000.pdf

And I would at least suggest my co-workers who are interested in the 13 bird families (in the table of page#8) that use cosmetic substances to read this overview.

I recall finding what looked and felt like patches of powder down on the flanks of Levant Sparrowhawks. Is there any information suggesting this might be so? I have not seen this in any of the North American accipiters.

Pingback: Shoebill Stork - Scariest Bird - Only Advert

I work at a wildlife center and while I often see powder down patches on the Yellow-Crowned Night Herons we get (we get a lot of babies), I did not realize that doves and pigeons have these. Are they in patches or spread throughout the body? I have noticed that unlike songbirds, the skin of doves and pigeons that is between the feather tracks is covered with fine feathers. Are those the powder down feathers?