Last month (late Aug 2010) I had the pleasure of spending some time at the Nature Conservancy’s Pine Butte Guest Ranch in Montana, where an irruption of Red Crossbills was in full swing. Each day around the ranch I saw and heard hundreds of crossbills, of two main call types, and these offered a great opportunity for study.

Beginning in 1988 with Jeff Groth’s paper documenting two distinct populations of Red Crossbills in the Appalachians, interest in these birds has steadily increased. Researchers (primarily Groth and Craig Benkman) have now identified ten different call types in North America, and there has been serious discussion of calling them all species.

For birders, these ten types are nearly indistinguishable in the field. The surest way to identify them is to make recordings of flight calls and then create spectrographs to study the details of those calls. Even if you manage to get a good enough recording to make a clear spectrograph, some calls are so similar, and variable, that it takes a practiced eye to distinguish them.

Furthermore, the calls are learned, and there are a few documented cases of birds giving more than one call type, and others that switched call types as adults to match their mate.

I’ve always been just a bit skeptical of the proposal to treat each call type as a species, but spending more than a week living with two types of crossbills in Montana has turned my opinion in the other direction.

First of all, the two types present there were easily distinguishable by ear. Each day I saw hundreds of Type 4 crossbills, with a sharp rising “chwit” call, and tens of Type 2 crossbills, with a lower, descending “kewp” call. Often I would hear other sounds that I attributed to the “toop” calls (mild excitement) of these types, or to bits of song. I only heard a few true flight calls that were not easily placed in either of these two types. Some of these were probably Type 3 crossbills with a higher “klink” call, but I felt confident about identifying nearly all of the flight calls I heard.

Granted, I assumed I was only dealing with two types, and I may have been missing other types and just lumping them into the two categories I created. It can be much more complicated when dealing with three or more types, but with just two it was relatively easy. Based on the information I had available there I was certain that Type 4 was the more numerous type, but whether the others were Type 2 or 5 was a matter of internal debate until I got home, made spectrographs of my recordings, and asked Nathan Pieplow for help.

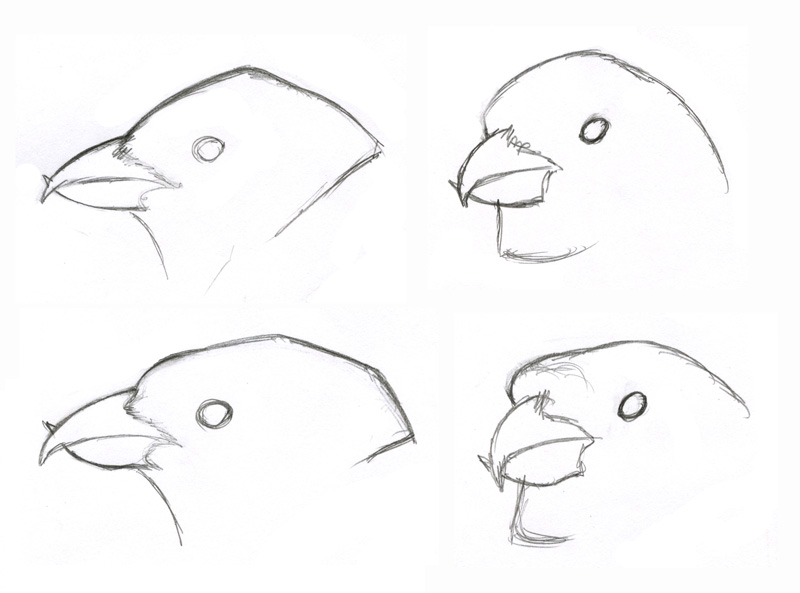

There were several things that made me think I was looking at two discrete populations that were acting like species. For the most part, I was able to distinguish the two types visually. The Type 4s were slightly smaller and more “delicate” overall, especially in the head and neck, and had a slightly smaller bill. The Type 2s were slightly larger and “more burly” with a thick neck and blocky head, and with a deeper and heavier bill. I thought I could see these differences whenever I watched a calling bird of known type, but the real test came on the several times I picked out a Type-2-like bird and then heard it call.

Nearly all of the confirmed Type 2 birds were in full juvenal plumage, unlike the Type 4s (which were adults and many worn and molting juveniles); and the Type 2s were consistently more heavily streaked and more contrasty on average than the juvenal plumage of the Type 4s.

The overall tone and quality of the song seemed to differ even more than the flight calls. I am less confident of this because song is extremely varied and I didn’t hear enough to really sort out all the variation, but whenever I noticed a singing Type 2 it immediately stood out from the more numerous Type 4s in pattern and pitch.

Finally, although the birds were all feeding on Douglas-Fir cones and eating salty grit on the ground, often in mixed company, in the air they kept to their own kind almost completely. Pure flocks of Type 4 crossbills would fly over, and whenever I heard Type 2s I would find them in their own small flock or as single birds. In other words, they mixed about as much as Red-winged Blackbirds and Brown-headed Cowbirds mix. (In contrast, Common and Hoary Redpolls seem to mix indiscriminately in flocks).

It seems that people who have spent a lot of time looking and listening carefully to Red Crossbills are persuaded that these call types are really significant. This was my first opportunity in the last 15 years to immerse myself in crossbills, and I came away really excited about the differences. They may be species or subspecies or they may not quite fit any of our existing categories, but these call types are definitely distinct populations and deserve all the attention they get.

Further reading:

As a starting point for birders Craig Benkman’s summary of Red Crossbills in Colorado has lots of good background info that applies everywhere.

Jeff Groth’s original website is still an excellent summary of the call types, with recordings and measurements

Nathan Pieplow at Earbirding.com has several blog posts about these topics:

- an excellent Introduction to crossbills – http://earbirding.com/blog/archives/31

- an index of Red Crossbill recordings at the Macauley Library http://earbirding.com/blog/archives/193

- A quiz that discusses ID features of some western call types http://earbirding.com/blog/archives/730

Matt Young’s Introduction to Differences in Crossbill Vocalizations offers the basics – http://ebird.org/plone/ebird/news/introduction-to%20crossbill-vocalizations

Ken Irwin recently described Type 10, and he has an extensive and very detailed website with lots of recordings. http://madriverbio.com/wildlife/redcrossbill/

Craig Benkman discovered Type 9, and has published extensively for two decades on the evolution and ecology of crossbills, pines, and squirrels. Many of these papers are available at his website (go to publications) http://www.uwyo.edu/benkman/

Could you bless me with a tenth of your sketching ability! I love your unique observations.

Great post — I agree with you that the call types act like species in the field, and usually flock separately (though not always). Prior to reading this I would have said there was absolutely no hope of identifying a crossbill to type in the field by looking at it, but perhaps there is, at least in certain circumstances! I’d love to hear more about the differences in song sometimes — crossbill song remains poorly understood.

Hi Nathan, I’ll try to get around to posting something about the songs. I didn’t start listening carefully to them until the last couple of days, and I was struck by some differences but also by how variable the songs are. In one long bout of singing the Type 4s would transition over a minute or more from loud, strong, rhythmic phrases to quieter, higher-pitched, squeaky and “sing-song” phrases. The first time I started paying attention to the songs I heard a strong rhythmic song from Type 4 and a high squeaky song from Type 2, and thought “This is easy!”. But later I started hearing the full range from Type 4s.

I was identifying the songs by the calls that were given in the context of the song. I know Irwin says that crossbills can use song phrases that seem to mimic other call types, and I heard many song phrases that sounded like odd flight calls, but the Type 4s and Type 2s I was hearing always seemed to circle back around to their own distinct call type frequently. That alone made the overall sound of the song quite different. Also, among the wide variety of phrases used, I’m sure there are particular sounds that are unique to each type.

In the end I was less confident, since the flight call was the only part of the song that I could really confidently identify to type. I had a feeling that the Type 2 song was generally slower and somehow weaker, but that may be because those birds were just less committed to singing than the more numerous Type 4s. The Type 2 song did seem lower-pitched overall, but that might also be simply because their flight calls are lower-pitched. Listening to the few recordings I made the differences sound less obvious than when I was hearing them in the field. More study required!

Were the Type 4’s singing much David? Seems that most types except for the eclectic in diet Type 2 stop nesting come late August/early September –that’s been my experience in the field and the literature suggests this as well. Here in central NY where I’ve been studying mostly Type 1, singing is quite rare past August 15-20th. In 7 years I’ve had only one bird singing past this date — a Type 1 singing Oct 18 two years ago — a very late date for this type. It would not surprise me however to see/hear the specialized generalist Type 2 singing and nesting well into October or later.

Hi Matt, Yes, the Type 4 birds were singing quite a bit. Whenever I ran across a flock of crossbills in the trees there would be one or two that were singing, sometimes from within the trees as they foraged, other times from the very top of a Douglas-Fir. I didn’t see any other behavior that suggested nesting. I heard less singing from Type 2s, but they were much less numerous and mostly juveniles (juveniles weren’t singing, as far as I know, just that there were few adults around).

I love Choteau! Thanks for bringing back memories of typing crossings out there when I was working for the Forest Service back in the 90s. I thought the types were pretty easy to differentiate back then, but maybe I was just young and foolish 😉

I’ve also gotten the impression that crossbills will sing when in certain social contexts, even though they likely aren’t nesting or about to nest. Irwin mentions that the mere presence of different types seems to initiate singing –my field observations support this, but as we all know there are few absolutes in the crossbill system. They also sing different songs in different contexts -My impression is they sing a more fixed song-type when about to nest.

The possibility of sympatric evolution in Red Crossbills is an exciting prospect, but there seems to be quite a bit of evidence to the contrary. It is especially problematic when one of the traits used in making the determination is not inherited but learned. Regardless as to how distinctive calls and songs are for the various crossbill types, it seems moot to use them as a taxonomic character (or for that matter identification purposes) if birds can learn different call types or switch call types as adults. That leaves morphometrics and genetics for making the determination, but if a crossbill of one type even occasionally pairs with another crossbill of a different type, then the progeny would have muddled inherited traits. Additionally, it has been demonstrated over and over again that a population adapting to a local food source can change bill morphology quickly, showing that this trait is very plastic and subject to rapidly changing environmental conditions. Crossbills currently seem to lack barriers to prevent populations from mixing- they (1) utilize a resource (conifer seeds) that is ephemeral across large areas so different types come into contact regularly especially if they feed on the same conifer seeds; (2) have the ability to shift to a new food source as necessary in a few generations through bill modification; and (3) have limited reinforcement of population boundaries by call/ song type . More sedentary populations, like the South Hills Crossbill and perhaps the Newfoundland type, seem to be the best candidates for speciation.

I understand all of your points, and for a long time I resisted the idea of multiple species of Red Crossbills for the same reasons. I’ll try to articulate a couple of points that tilted me in the other direction. This is based mostly on reading some of Benkman’s papers, to give credit where it’s due, but I’m adding my own speculation in some cases.

Calls are learned, from the parents, but they are essentially just markers that allow birds with similar bill structure to find each other. Since bill size and the structure of the palate allow a crossbill to forage very efficiently on one narrow size range of conifer seeds, and since the resource is patchy, it is advantageous for the birds to travel in a group with other birds that all have similar preferences. That way the flock can quickly assess a tree, and an area, and move on if their preferred food is scarce. A crossbill that switched call type would be at a serious disadvantage, since it would end up with the wrong group, foraging in trees where it is less efficient. Detailed studies that have looked at this question have found call-switching to be extremely rare, as one would expect logically.

That said, the differences in calls and in bill structure are very small and in many cases overlapping, so it’s possible that this is a very fluid system – rapidly evolving, merging and splitting as conifer seed production favors one type of crossbill and disfavors another. I suspect it’s much more stable than that, since the conifer species involved have been around for a very long time, and the size of their seeds doesn’t seem to change very rapidly.

In any case it is clear that what we are seeing right now is a series of discrete populations of Red Crossbills, and to maximize their foraging efficiency they have strong incentives to stick together with their own kind. Whether we call them species or not, “sympatric evolution” seems to be happening.

Hi AJ,

For the most part, I completely understand why people are doubtful about crossbill Call-Types being species, but I suggest everyone read these three “new” papers.

Early learning of discrete call variants in red crossbills: implications for reliable signaling

Kendra B. Sewall

Limited adult vocal learning maintains call dialects but permits pair-distinctive calls in red crossbills

Kendra B. Sewall, a,

Social experience modifies behavioural responsiveness to a preferred vocal signal in red crossbills, Loxia curvirostra

Kendra B. Sewall*, Thomas P. Hahn 1

When crossbills are feeding on alternate food sources, it’s often only for a short time (few months) and many times it’s not when they’re nesting or nesting with any great success –the offspring will not reflect the morphology of what they’re feeding on unless they form residency for several generations (years) while feeding on alternate food resources –this doesn’t really happen. Each Type has a core zone, and in this core zone they have a key conifer(s) for which they’re most efficient at foraging on. Some years key conifers fail to produce good cone crops, or other conifers have matured cones and seeds are more easily accessible (spruce seeds are more accessible by all Types in late summer/early fall) –under such scenarios, they switch to other conifers that offer the highest energy profitibilities. At the end each cone cycle year (June-May) Types reassemble in their core zones with respective key conifers.

Crossbill flight calls are stable over time and the flight call depicts morphology and not the other way around. Birds don’t change their calls -at most, this is an extremely rare event! — Benkman found one bird to do so out of 1700+ birds –none of Groth’s birds or Sewall’s changed call. In all my experience I’ve never heard a bird change it’s call to match another Type…and, I’ve often encountered several types in the same area several times. Besides, many of us have heard a warbler of one species pick up the song of a different adjacent warbler species– I can give several examples of this.

Strike that, Benkman’s sample size was 3400 birds (Types 2, 5, and 9), 1700 pairs.

Has anyone done work with Red Crossbills outside of the North America? As I understand, there are populations in Eurasia and Africa, as well as Central America. Do these represent completely different sets of call types?

Hi Owen, Yes, quite a bit of work has been done in Europe, where there are multiple call types as in North America. In fact, Parrot Crossbill and Scottish Crossbill, both considered species, are really just slightly more obvious examples of the same variation in bill size and call type seen here. And they have a small number of call types that have been discovered within the widespread Common (Red) Crossbill.

Pingback: La complessità nascosta del canto degli uccelli – Y Chat

Pingback: The Hidden Complexity of Birdsong – BIRDS

Beautiful sketch of birds, love to see