Lots of birds have a habit of pumping (or wagging) their tails. It’s mostly open-country birds like phoebes, wagtails and pipits, Palm Warbler, Spotted Sandpiper, and others. Many hypotheses have been suggested to explain why the birds do it, but nobody came up with an answer until Gregory Avellis in 2011.

He studied Black Phoebes in California, and tested four different hypotheses to see if tail pumping was related to:

- balance – but tail pumping rate did not change depending on where the phoebes perched

- territorial agression – playback of Black Phoebe song caused a territorial reaction but did not change the rate of tail pumping

- foraging – tail pumping did not change significantly whether the birds were foraging or not

- predators – playback of the calls of a potential predator – Cooper’s Hawk – caused tail pumping rate to triple

Avellis concludes that tail pumping is a signal meant to send a message to the predator. It tells the predator that the phoebe has seen it, and therefore the phoebe is not worth pursuing.

Avellis, G. F. 2011. Tail Pumping by the Black Phoebe. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 123: 766-771. abstract

I’m not sure this actually answers the question, though. There are other hypotheses to test. I always figured the tail movement of phoebes was related to the tail-wagging or pumping behavior of most stream-side birds: a means by which to break up the body outline against a moving background of water. Also, many birds flick their tails anxiously when mildly alarmed, could this not also simply be the “burning off” of nervous energy the way a cat does? For example, when a Green Heron (or a tiger-heron in the tropics) is holding still for long periods waiting for a prey item to come close enough to capture, it often flicks its tail. Presumably, this burns off nervous energy away from the view of the potential prey. Perhaps this latter situation is not quite the case for a phoebe, but it could be something that has spawned tail movements in tyrants in general.

Hi Dan, good points. Like you, I had settled on the idea that these tail movements were a sort of “cryptic motion”, maybe it helps them blend into the background, I thought it might confuse predators about which end of the bird was the head, somehow. But now I’ve learned that there is a lot of research (mostly on ground-squirrels and lizards) supporting the idea that many displays like tail pumping are “pursuit-deterrent” signals. They send information to the predator (e.g. “I know you’re there and I’m quick enough to escape”) which causes the predator to rethink and at the same time alerts other potential prey nearby. A recent paper on ground-squirrels is Putman and Clark 2014 (pdf here). That study looked at the use of these displays in the absence of predators, and suggests that it can be valuable to the potential prey to signal vigilance even when they don’t know of a predator.

No no you’re all wrong !

Not a deterrent . Not burning nervous energy.

( OBVIOUSLY if it were a deterrent it would be done all the time as a natural selection of behavior by evolution..)

It meant to serve the second purpose as the squirrel tail flagging, and the serpentine undulation of the cat as it sits focussed on prey: to serve as a primary target to an attacker from the rear! I am fairly sure though cannot prove it, that many birds can live till the next moult without a tail. I have seen such a one flying and landing on a branch , using a dip technique to slow down before landing.

Finally the cats tail serpentine movenment may serve second function to scare off some animals…

..I’m back… 😉 ….furthermore look at the number of reptiles from which our birdies are descendants that have fragile easily detachable tails. Lizards wag them too when they feel stalked, I suppose. And certainly they break off to spare the rest of the body.

Do we know if the lizard or bird can both control the degree of fragility of the tail? By muscle or hormone?

Thanks for your time bird folks!

Hi Theodore,

To respond to your question – why don’t phoebes tail-pump all the time? Here are my thoughts:

– the study David was reporting on mentioned that the Black Phoebes pump tails MORE FREQUENTLY in the presence of a predator, not that they only pump tails in the presence of a predator. Other studies on the Eastern Phoebe produce similar results to this too (see reference below). Phoebes DO pump tails even when not in the presence of a predator, and thus potentially when they are but unaware of it too. Could that afford them some protection too?

– If tail-pumping occured at the same rate all the time, then all it could do to deter predators is communicate “I am a phoebe and tough to catch” and never “I see you, therefore I am VERY tough to catch right now”. So there’s that difference, and I could see why it might evolve as a predator-deterrent in the way suggested by the literature: the faster tail pumping could be more effective at deterring prey, and could evolve to occur when phoebes truly are toughest to catch.

– some point out that phoebe tail-pumping could have a cost because it could reveal location to predators who haven’t spotted them yet, and thus make them more vulnerable to attack (again, see reference below). My thoughts would be that, if the tail-pumping really does sometimes work to deter predators and benefit the phoebes, then it must work effectively enough to overcome this potential cost. And that’s maybe what the results of the studies suggest? Otherwise, it’s hard to explain why tail pumping increases in the presence of the predator if it is something that could be costly to them.

To be fair, your points about an alternate function are not totally unwarranted – I’d imagine that for tail-pumping to evolve as a predator-deterrent, the phoebes would have to have been already in the habit of pumping tails. My thought is that this habit got repurposed into being a predator-deterrent (and maybe that helps explain why it tail-pumps without any predators around, but increases the rate at which this occurs in the presence of one). But… is the habitual tail-pumping something they just happened to do before, or maybe did for some other reason too? I don’t know.

Thanks for your thoughts.

Reference:

Carder, M. L., and Ritchison, G. (2009). Tail pumping by Eastern Phoebes: an honest, persistent predator‐deterrent signal? 1. Journal of Field Ornithology, 80 (2), 163-170.

Hi David,

I’m happy to see we are thinking in similar ways! http://ornithologi.com/2015/02/22/tail-pumping-behavior-in-the-black-phoebe/

I like Dan’s comment. There will always be other hypotheses to test, and in other species as well. Some friends and I have discussed the topic a bit. One interesting idea that was brought up was the difference in the tail pumping habits of eastern and western Nashville Warblers. And the bobbing behaviors of species such as Spotted Sandpiper, American Dipper, etc. It would be of interest to test these habits in a similar way to see if the behavior has the same role between species, and in the case of the NAWA, why it differs between two subspecies.

Hi Bryce, I found your post when I googled to do a little more research this morning. It’s funny that within a month we both highlighted a paper from four years ago – thinking alike, I guess. Thanks for your comment. I hadn’t thought about the tail motions difference between subspecies of Nashville Warbler. I’m actually a little skeptical of that difference, but if it’s real it would make a very interesting test subject for this question.

we must also consider humans as a potential predator or variable– I WOULD THINK A PROJECT LOOKING AT PEOPLE VARRIABLES SUCH AS GENDER, COLOR OF human presentation- clothes color, hats etc ,and activity level would be obvious things to look at- we all know we sush each other not to scare birds away Jeff kline

The “person” factor is obviously a standardized variable because the field methods were (likely) performed by this sole author. Furthermore when a person conducts a behavioral study on a wild population, they do as much as they can to not disturb the population (outside of their experimental treatments of course).

Vermilion Flycatchers are among the habitual tail dippers.

This morning I observed some stub-tailed nestlings, which appeared

on the verge of fledging, dipping their little 1.5 cm long tails.

Could the nestlings really be signalling their readiness to flee?

Or just practicing an inherited habit when the people came close?

I don’t mean to suggest that tail-wagging involves any conscious decision-making by the phoebe. If we could ask a phoebe why it wags its tail all the time I suspect the answer would be “Do I? I don’t know, it’s just a habit”.

Tail-wagging can be thought of as a “signal” that the phoebe and the hawk both understand, but it is a very basic and instinctive signal, not really a conscious attempt to communicate. When we get nervous we fidget, when phoebes get nervous they wag their tails, and when a predator sees fidgeting or tail-wagging it gets the message that this is a healthy and alert animal and probably not worth chasing. That aspect – fidgeting or twitching under stress – is universal, something we “just do” because it is hard-wired and instinctive.

What varies by species is exactly what we do to send the signal. Phoebes and a few other species of birds wag their tails, others flick their tails up, others flick their wings, others bob their heads, call, etc. It is all just different ways of sending the same message. And the stub-tailed baby Vermilion Flycatchers have the same instinctive nervous habit as their parents.

Hi David,

Interesting points you make here. I would be willing to bet the behaviour of the Black Phoebe is instinctual too. What about the predator’s behaviour? It was Cooper’s Hawk in the case of the study, I believe. I would lean towards their response being more a learned behaviour – they could learn to associate attempting to capture a tail-pumping phoebe as a challenge that often proves costly. Or might that become instinct too? Not sure I know enough about instinctive vs learned behaviours though.

My pet Java sparrows wag their tails left-right from time to time, and I don’t think they feel in danger from predators inside our house. I’ll try to pay more attention to the context next time I see it. I seem to remember that it sometimes happens when they’re perched on my finger after having taken a bath and finished drying off and preening.

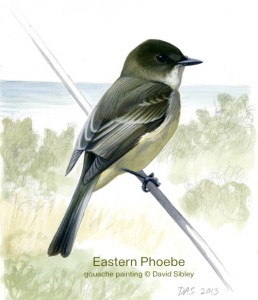

With apologies for bringing a commercial question to the list–any chance of a Phoebe painting or print becoming available at some point? Would love to purchase for a birder friend whose newborn daughter is named Phoebe. Thanks.

I’ve always assumed tail-pumping was associated with predatory behavior. Many of the species that exhibit this behavior use hunting strategies where they make sudden, sharp turns in midair, and my thought was that the behavior kept the tail muscles stretched and at the optimal operating temperature. The tail wagging would then be a signal to predators that they’ve not only been noticed by the bird, but the bird is more than ready to give the predator the high-speed, rapid-swerve chase of its life if it trys anything. Have there been any studies investigating this aspect of tail-wagging?

I’ve noticed their tail pumping to also be just a consequential bodily reaction to their cheeping. Like when we talk, sometimes we incorporate the use of body language.

Is it the case that Eastern Phoebes pump the tail virtually all the time? I’ve used this behavior to distinguish Phoebes and Peewees. Is that valid?

Do Chipping Sparrows flick their tails up and down? I need this information for a children’s book I am writing.

Question–Do chipping Sparrows flick their tails up and down? I need this information for a children’s book I am writing. Thank you!

The American Kestrel flicks his tail downwards as he enjoys dining on his prey. Why can’t it be like a nervous twitch, an inherited trait that serves no practical purpose and is triggered randomly?

Let’s not lose sight of the fact that these birds may APPEAR to be doing these repetitive motions all the time when in fact they aren’t. We have no idea what they’re doing when we’re not watching and our presence may trigger the behaviors. If we know the birds are there, chances are pretty good they also know we’re there and see us as potential predators.

We have a pair of phoebes nesting at our camp, with babies who are nearly ready to fledge.

The parents each have their own favorite perches when standing guard over their nest, but their tail-flicking patterns are decidedly different…one just bobs up and down, and the other flicks in a nearly circular motion. Are these differences distinguishing patterns between the genders?

Pingback: How Do I Identify A Yellow Warbler? – Ploverbirds.com

Pingback: Are Palm Warblers Rare? – Ploverbirds.com

Pingback: What Bird’s Call Is Phoebe? – Ploverbirds.com

Pingback: The Understated Beauty of Eastern Phoebes – Being with Birds

Nice. Your article have much information that I need. Thanks guys.